Studio Tour: Renae Barnard

The Studio Tour series offers an inside peek into the work environments of WTP artists, as well as insight into their creative process within these resonate spaces.

By Jennifer Nelson, WTP Feature Writer

Renae Barnard is recognized by the United States Green Building Council (USGBC) as a Leadership in Energy Accredited Professional (LEED AP) and by the International Institute for Bau-biologie® & Ecology as a Building Biologie Practitioner. She has recently completed projects in cooperation with the National Immigration Law Center and the City of Santa Monica Department of Cultural Affairs. She is a recipient of the Sue Arlen Walker and Harvey M. Parker Memorial Fellowship, the Armory Center for the Arts Teaching Artist Fellowship, The Ahmanson Annual Fellowship, Lincoln Fellowship Award, and Christopher Street West Art and Culture Grant.

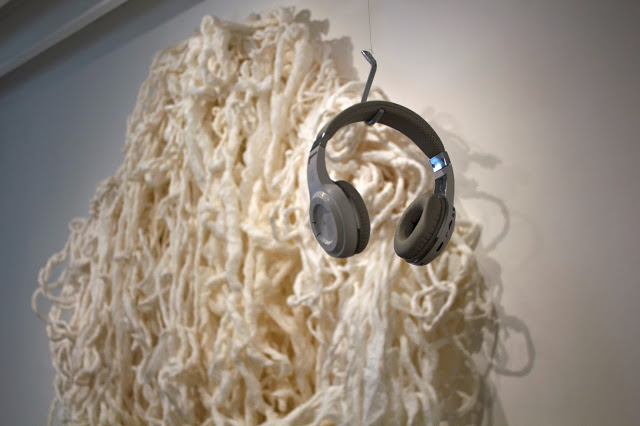

For Renae Barnard, her studio is on the go. She weaves in her lap; bowls of salt mixture are evaporating on her front porch; she may rent out temporary spaces around Los Angeles as her projects require. For her most recent public work, at Bergamot Station, Santa Monica, California, she shared space with other artists in a large commercial building in Boyle Heights. “Sharing space with other artists on a short-term basis allows me the access to equipment I may need,” she says, “like a spray room, wood shop, or kiln without the financial burden of permanent overhead.”

Nevertheless, she faces challenges when sharing space, the main one in Los Angeles, not having a parking space. This meant that Barnard had to haul sculpture materials down a sidewalk to a metered parking space. “It’s not always the most convenient, but it’s manageable,” she says.

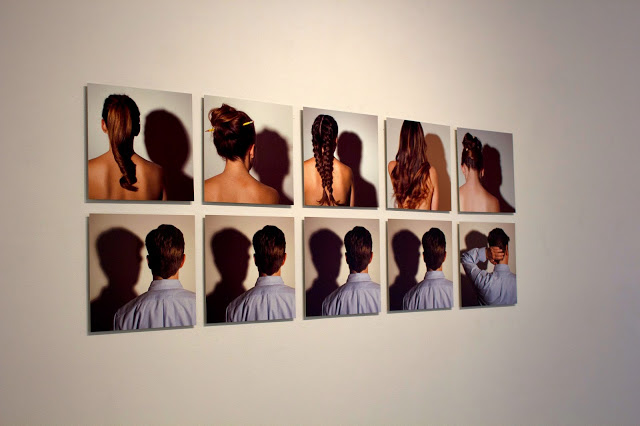

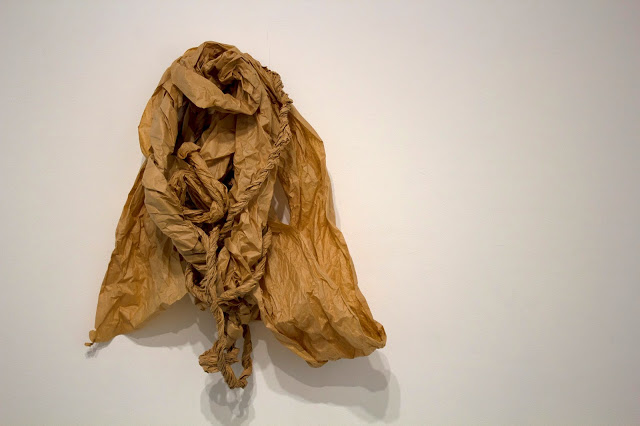

For two years, her studio was a tiny white box in Claremont, a city thirty miles east of Los Angeles, where she kept weaving and sewing materials, as well as tripods for her photography. Many of the materials were incorporated into works such as “Displaced Tinder,” a sculpture of twisted medical exam paper wound around school chairs.

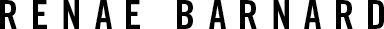

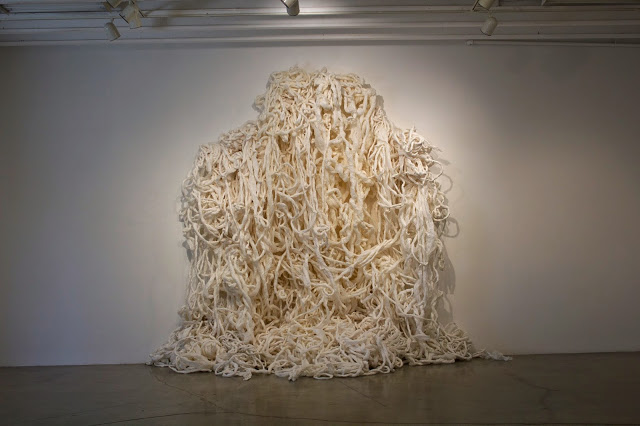

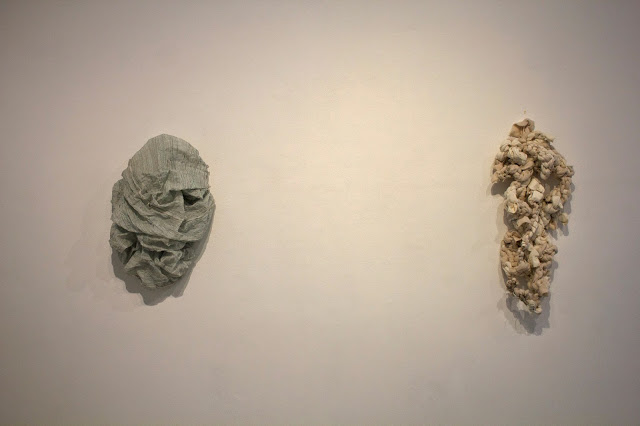

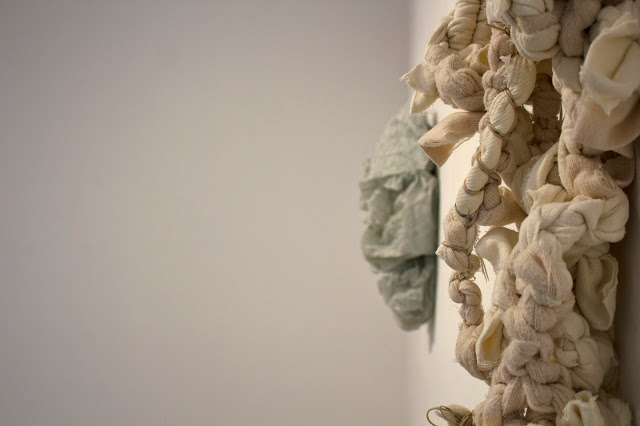

With time, she has realized form through repetitive movements like weaving, sewing, and twisting motions. Now she is experimenting with other modes of accumulating form, including a series of fiber sculptures of cotton batting, upholstery foam, and polyester fiberfill scraps discarded by furniture manufacturers. These materials are supplemented with water-based paints by Dunn Edwards, salt, water-based glues, and vinegar. “I’m interested in the ways in which basic chemistry might create form beyond those achievable with my hands,” says Barnard.

To work, Barnard requires silence and solitude. She doesn’t want music, visitors, or lingering clutter. Her process is generally exploratory, allowing room for discovery along the path and at the finish. There’s an undercurrent of chaos that she’s always wrestling with. The outcome is not a literal display of the problem, nor is it offering a solution. It is a record of the thought process and the struggle: “I’m interested in examining our situations and hopefully moving beyond the place where we stand now.”